Author: Arnaldo Cruz, FOMB's Director of Research and Policy

Given the challenges of the central government and the fiscal sustainability of many municipal governments, this might be the best chance Puerto Rico has to truly transform the entire government structure.

The Central Government

The Government of Puerto Rico has historically disappointed in providing efficient, effective, and responsive services to the people of Puerto Rico. According to a recent national survey by El Nuevo Día in March 2020, more than half of the population believes the government is not prepared to respond to future emergencies. In a recent survey conducted by the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, 85% of the population had little to no trust in the government. But this is not a new thing in Puerto Rico. Another survey in 2016 conducted by the Research and Survey Institute at Turabo University found that 90% of Puerto Rico residents did not fully trust the government.

For many years, both the public sector and the private sector have been talking about reforming the government. However, even with this apparent consensus, there seems to be little progress in the way the public structures are administered on the Island. Since the arrival of PROMESA, the Oversight Board has encouraged Commonwealth agencies to find ways to increase efficiency and improve the way services are delivered to the people of Puerto Rico by reducing or eliminating overlap in the government. Unfortunately, the implementation of fiscal measures has been slow and incomplete in most agencies so far. Although some local stakeholders initially coined these fiscal measures as austerity, most of the budget reductions were supposed to come from efficiency initiatives, which only reduce personnel in non-client facing functions (administrative roles such as finance, human resources, and information systems, as well as some facilities support) and achieve savings with digitization and improved procurement practices. The objective of these measures was not to reduce direct government services but to deliver such services as efficiently as possible while keeping within budget constraints. The public management and cost-saving rationale is quite simple. If you only need 30 people to manage procurement for all government contracts, why would you want to use 100? The same goes for other non- client-facing departments, which most of the agencies insist on having. Does it make sense to have dozens of procurement offices, print shops, HR Directors, and finance departments in the central government, and employ hundreds of people to perform equivalent functions? Even the most ardent anti-austerity advocate would argue against 114 procurement, HR, and IT departments throughout the government.

Ironically, the Commonwealth has a heavily centralized structure, as opposed to states that share many responsibilities with counties and municipal governments. Imagine how difficult it would be to consolidate procurement offices of the City of Chicago with Cook County and the Illinois state government. That is why fragmentation of administrative functions is so puzzling in Puerto Rico. Even common areas of government suffer from heavy fragmentation, overlap, and duplication. Take health as an example, where we have a public corporation (ASEM) running Puerto Rico’s most important hospital, the Medical Center, and a Department of Health running three other major hospitals. Meanwhile, the University of Puerto Rico, another public corporation, runs two other hospitals, while the Commonwealth’s own public monopoly for worker’s compensation insurance has its own public hospital, called the Industrial Hospital. Finally, the Corrections Department runs another hospital as well. No one seems to know why we have different entities within the Commonwealth running hospitals. As expected, none of these hospitals share basic services or have common planning or procurement processes, as they all work as independent units. They even have different collective bargaining agreements, which leads to huge disparities in the compensation of nurses and public health workers within the same government.

The proliferation of departments, public corporations, and agencies in Puerto Rico has severely hindered the ability of the Commonwealth to function. Beyond budgets going to duplicative positions, the fragmentation has curtailed effectiveness, accountability, and transparency in the government.

Imagine how difficult it is to constantly audit dozens of procurement departments to ensure processes were done properly, and prices were competitive. Or to consolidate government payroll and HR information to ensure there is consistency with credentials and competencies. The current model has dramatically failed the people of Puerto Rico.

As part of the 2019 Fiscal Plan, the Oversight Board required the Government to consolidate the 114 agencies into no more than 42 agency groupings and independent entities. This consolidation would have then facilitated the centralization of back-office functions, digitization of redundant tasks, and elimination of unnecessary administrative positions. It would have also helped with streamlining services and cost-efficiency.

However, so far, the Government has not made meaningful progress in achieving savings through agency consolidations or improving operational efficiency. Notwithstanding, the Government was able to meet budget targets in FY2019, albeit through ineffective tactics. For personnel savings, the Government has primarily focused on broad-based early retirement programs (e.g., the Voluntary Transition Program or VTP), which has led to shortages of key personnel in many agencies, who stubbornly insist on keeping back-office personnel. The result is a less efficient and effective government for the people of Puerto Rico.

Some local stakeholders argue that the Oversight Board should reverse budget reductions so that government agencies can hire key personnel and improve services. But who guarantees that agencies will hire the right personnel to cover those shortfalls? What if they hire more people in outsized areas, like HR or office management, and leave critical areas uncovered? We must remember that there is no overarching personnel office in the Commonwealth in charge of all hiring and firing, as each agency manages its own process.

Without changing the way, services are delivered and/or determining which government activities will be discontinued, simply reducing headcount risks exacerbating already outdated government operations. If the Commonwealth has been unwilling and unable to transform government services, what then?

Are 78 municipal governments the answer?

Some in Puerto Rico argue that municipal governments have done better than the central government in providing services to the people in Puerto Rico. But there is ample evidence to suggest otherwise. A recent report from the Office of the Comptroller of Puerto Rico revealed that in the last couple of years, 37 municipalities had invested about $63.6 million in capital projects that were never finished. Most of the buildings mentioned in the report are structures that are repeated throughout all the towns, such as coliseums, theaters, basketball courts, convention centers, and water parks. The Comptroller points to a lack of planning, budgeting, and permitting as the main reasons why these projects were never completed.

The Office of the Comptroller, who audits municipal governments, constantly finds irregularities in areas of purchasing, personnel, and fund management. In an interview with El Vocero in 2019, the Comptroller stated, “As for the municipalities, in the vast majority of audits we find issues with procurement, either they don’t request quotes on purchases or quotes are fake.”

The other challenge with municipal governments is fiscal sustainability. ABRE Puerto Rico, a local nonprofit, has been publishing a fiscal health index for municipalities since 2015. In their latest publication (the fiscal year 2018) the organization acknowledged great improvements with fiscal indicators in the short term, but this did not change the long-term financial position of municipalities in Puerto Rico. About half of the municipalities still have a negative fund balance, and almost half still depend on central government revenues. In municipalities such as Las Marías, more than 80% of operational revenues come from the central government. Although some municipal governments have shown restraint and fiscal discipline over the years, around 65% of municipalities still have a negative (restricted) net financial position.

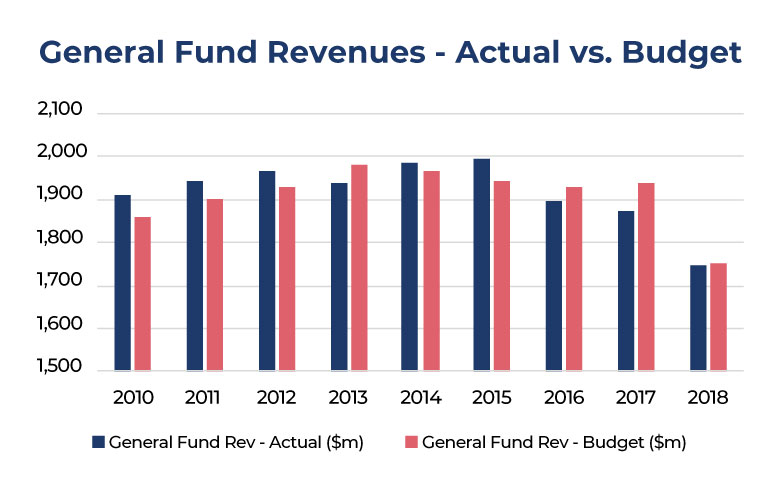

A review of historical trends of municipalities’ budgets and generated revenues validates the challenges with operating with declining resources. Analysis of data produced by ABREPR, from “fully reporting” municipalities, demonstrates a pattern of inability to operate within budget targets.

Exhibit A

General Fund Revenues, Actual vs. Budget

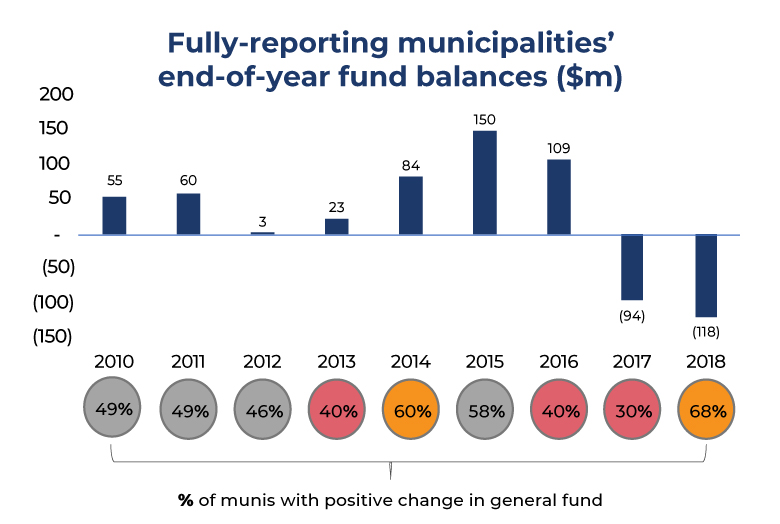

Often less than half of the fully reporting municipalities recorded a positive change in general fund balance in any given year (due to budget shortfalls), and about 40% are dependent on Commonwealth appropriations to operate.

Exhibit B

Fully-Reporting Municipalities’ End-of-Year Fund Balances ($ in millions)

From FY2010 to FY2018, these municipalities’ aggregate General Fund balances sunk from $55 million to negative $118 million. Their repeated budget shortfalls put a further financial strain on the following years, driving negative fund balances that require persistent Commonwealth support or increased borrowing.

Given the challenges with funding, municipalities frequently-issued debt to meet operational expenses. Municipal debt surpassed a whopping $4 billion by FY2014. The Government Development Bank historically served as the ultimate backstop for municipalities, and the sole source of liquidity. Act 64-1996 gave the GDB the exclusive authority to approve all the financing instruments (bonds or notes) of the municipalities, including the instruments financed by the Bank itself. This financing scheme was very damaging, both for the Bank and for the municipalities, since it artificially evaluated the risk of municipalities, which led to easy access to credit.

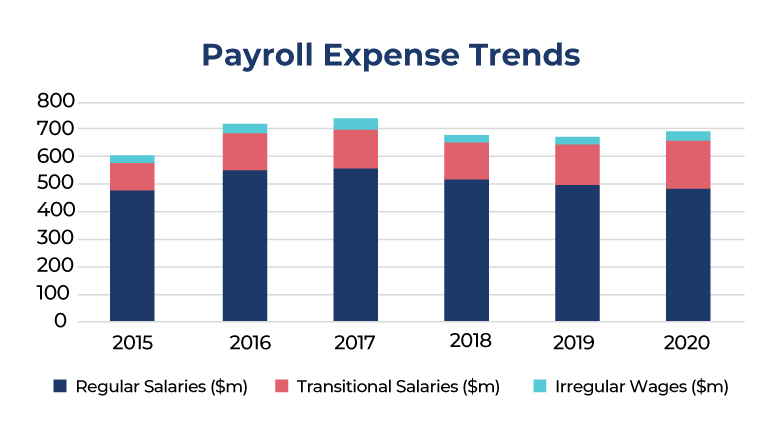

While the municipalities miss revenue targets, costs are also rising. For example, most municipalities have made no model changes to payroll expense budgets. The lack of salary and wage reform has led to payroll expense increases since 2015, despite employing fewer people and supporting a reduced population.

Exhibit C

Payroll Expense Trends

Many mayors argue that municipalities take on Commonwealth responsibilities all the time due to their failure to provide basic services.

Many point to this as the main cause of their budget deficits, particularly during emergencies. During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, municipal governments did take over some central government responsibilities, like food delivery, and have shown leadership with testing and contact tracing. But many times, these actions are not intentionally planned. Thus, municipalities have a hard time keeping track of those expenses, which is critical to qualify for the FEMA reimbursement process under the National Emergency Declaration. Furthermore, given the centralized accounting and data collection of the Commonwealth, it is hard to segregate costs and services at a municipality level. That being said, the argument that municipal finances have deteriorated due to the hurricanes is patchy.

The financial situation was unstable in most municipalities back in 2013, when there were no hurricanes. By way of example, for the fiscal year 2013, 64% of municipalities ran a revenue shortfall in their general fund, 90% had negative net assets (unreserved), and 43 municipalities maintained accumulated deficits in their generated fund. This was all before the GDB bankruptcy and the new Oversight Board.

Meanwhile, Puerto Rico’s population, which has fallen by ~18% over the last decade, is projected to decline more going forward, further depleting the tax base in many municipalities. Elevated unemployment due to COVID-19 related job losses will reduce property tax collections, SUT, business licenses, and other revenues, handicapping municipal finances even more in years to come.

The current de-concentration model, where the central government disperses public services to regional offices without the authority to make decisions, has proven to be expensive and highly ineffective, which unfortunately has been made more evident during this recent crisis. On the other hand, the 78 municipal government structure has proven to be fiscally unsustainable for Puerto Rico, as well as inadequate to solve key policy issues, due to lack of scale and capacity of most municipal governments.

Under this precarious scenario, Puerto Rico must urgently adopt a series of bold ideas to improve accountability, sustainability, and service delivery, not just with municipalities but within the entire government structure.

What to do then?

The Oversight Board reduced the Commonwealth budget to encourage agency consolidations and efficiencies. As stated before, agencies chose other initiatives instead to meet budget targets like VTP’s to reduce personnel, which ended up affecting capacity in key areas.

With municipalities, the Oversight Board encouraged voluntary service consolidations between municipal governments. Consolidating services across multiple municipalities could have reduced costs by leveraging scale, especially in areas of services provided directly to residents, including public works and infrastructure. As with the Commonwealth, Municipalities have not made any changes to their model, and don’t appear to want to do so in the future. In fact, reducing their Commonwealth contributions has probably led municipalities to reduce budgets in critical areas (in lieu of reducing employee benefits), as happened in the Commonwealth.

On the mainland, municipal governments do administer most of the essential services, from public schools to airport operations. In Puerto Rico, however, it is quite the opposite. Policing, prisons, public schools, utilities, ports, airports, roads, public transport, and health care are funded and operated by the Island’s central government. Thus, municipalities in Puerto Rico have far fewer responsibilities than municipalities elsewhere in the United States. For example, while most municipalities have the police force, it is the state police who are mostly responsible for security in Puerto Rico. Thus, it is hard to make the argument (with facts) that municipal governments are primarily responsible for public services on the Island. If you compare budget and program responsibilities, the Commonwealth is responsible for more than 90% of government program expenditures in Puerto Rico, while elsewhere in the US, according to the US Census, local governments are responsible for more than half of the state’s public expenditures.

This does not mean that municipalities in Puerto Rico do trivial things. They provide some crucial services to citizens and sometimes complement important services of the central government. As well, during the recent natural disasters, they demonstrated their value in the response. The recent pandemic has further demonstrated the central government’s lack of capacity to respond to the crisis, which little to do with inadequate budget or a lack of resources to respond. Rather, a centralized approach has proven, repeatedly, to be inadequate to effectively manage various government programs in Puerto Rico.

Given the central government’s struggles with providing basic services and municipalities’ lack of fiscal sustainability, it might be time to rethink the entire government structure.

Many in Puerto Rico (including mayors) are talking about decentralization as the way forward. The logic goes, if the government is closer to the people that it is serving, then it can be more efficient and responsive to citizens. Most of the literature does support that a decentralized system of government is more likely to result in enhanced efficiency and accountability than a centralized one. But there are gaps between theory and practice, as some decentralization efforts (in the US or around the World) have failed and ended up making things worse for citizens. Thus, careful design, discipline, and practicality are prerequisites to a successful decentralization effort.

Interestingly, the Commonwealth already has a heavily dispersed service infrastructure. Almost all central government agencies have field offices and employees in every municipality. Sometimes there are multiples offices within the same umbrella (i.e., Family, ADFAN, ASUME, ACUDEN). The Medicaid program at the Department of Health is a good example of this regional presence. There are more than 70 eligibility offices across the Island, while the entire state of Florida has only 13, and New York City has 19 to serve 8 million people. The Department of Health spends more than $20 million a year to sustain these regional offices. There are plenty of other central government structures all over the Island, from police headquarters, prisons, fire stations, voting offices, etc. The problem is that decision making is heavily centralized, and that is a very bad combination, as you are spending a lot of money to maintain a local presence but remain highly unresponsive to citizens. In addition, there are municipal offices that are not integrated with the central government’s regional infrastructure. In many municipalities, there are central government and municipal offices next to each other.

As a result, the government of Puerto Rico can be summed up as, public policies created by municipal governments with narrow viewpoints, and a central government that is too far from local conditions to be effective. At some point in time, these government structures were probably needed to provide necessary services. However, as problems and issues in Puerto Rico have changed over time, previous structures may no longer be necessary or may need to be redesigned.

The Third Way

Given that there are various decentralization approaches, one should be careful with using the term loosely. Considering the realities in Puerto Rico, the most logical approach would be along the lines of the delegation of both decision-making and the administration of public functions. To avoid a re-arrangement of political/electoral boundaries, local bodies that are delegated responsibilities would still need to be accountable to the central government (as municipalities do right now).

Many mayors want to transfer central government duties to all 78 municipal governments. There are several problems with that approach. The vast majority of municipalities do not (individually) have the operational or financial capacity to manage Commonwealth programs.

According to a FEMA assessment in 2018, only 19 of the 78 municipalities had hazard mitigation plans, most lacked a detailed inventory of municipal assets, and many reported losing significant human resource capacity after the hurricanes. The initial FEMA assessment also flagged municipal governments’ lack of capacity to secure and manage federal funds. Many also lack the economies of scale necessary to be efficient with programs such as ASUME, ADFAN, or Vivienda. There are some fixed costs required to manage each central government program (IT, key personnel, program-specific knowledge/capacity).

Establishing that infrastructure in each municipality is costly and unnecessary, particularly given our fiscal constraints. Even if you consider transferring central government personnel to municipalities to truly decentralize decision-making, you need to build capacity on many levels. Even with well-intentioned and capable mayors, most of the municipal governments in Puerto Rico do not have such capacity. Building that capacity in every municipality will turn out to be more costly than the current cost of regional offices (and then some).

Another issue with decentralizing to all 78 municipalities is scope and scale. Nearly all major problems in society, from economic to social, are region-wide in scope, and therefore cannot be solved by municipalities acting independently. It is not realistic to think that a municipal boundary in Puerto Rico has all the social and economic assets to successfully implement coherent and effective socio-economic development strategies. Instead of shifting all devolved authority to 78 municipal governments, the Commonwealth should help create regional institutions more capable of solving key problems.

A regional framework can be better fitted to tackle issues and formulate solutions around regional transportation planning, supply chain support, watershed planning, flood mitigation, environmental and resource conservation planning, among others. Moreover, a regional entity can successfully implement coherent and effective economic development strategies and engage in true regional planning and decision-making to be able to receive more federal funding in these areas. Creating this capacity at a regional level is more viable, realistic, productive, and useful than attempting to create 78 smaller commonwealths.

Towards a Regional Approach of Government

This is not the first-time regionalization of government services has been discussed in Puerto Rico. In 2016, Estudios Técnicos, a consulting firm, published a study where it recommended consortiums among municipal governments to manage administrative functions, garbage disposal, and road maintenance. In 2014, Governor García Padilla created a decentralization commission that included public officials, mayors, and academia. The commission published a report in 2014, where it also recommended the regionalization of government services. More recently, former Governor Rosselló introduced the concept of counties via executive order.

All those reports recommend legislation as the best path to make any transformation sustainable. So far, legislation around this issue has gone nowhere. Instead, governors and legislators have preferred to delegate more powers to many small, fragmented local units, rather than to create regional bodies.

But given the challenges of the central government with providing basic services and the sustainability of many municipal governments, this might be the best chance Puerto Rico has to truly transform the entire government structure.

The Oversight Board welcomes the discussion around the decentralization of government services. However, the design of any such model must meet certain parameters in order to be consistent with PROMESA.

Municipal Cost Savings

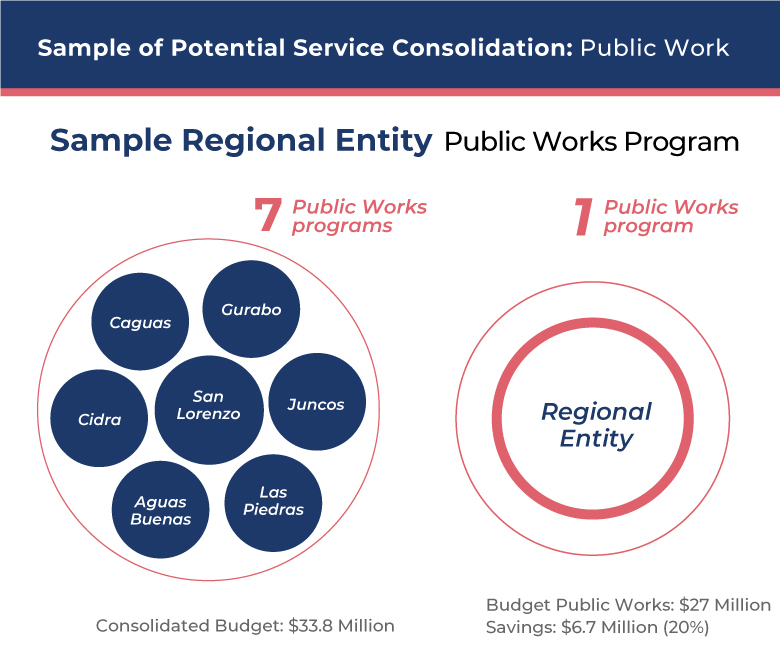

The proposed regionalization must reduce the costs of services provided by municipalities through service consolidation. For example, if public works services are consolidated under a new regional entity, operating expenditures of such activity must be reduced as a result of service consolidation. In other words, existing municipality budgets and employees would need to be reduced in order to achieve cost savings. Will use an example to illustrate.

Exhibit D

Sample of Potential Service Consolidation: Public Works

Under this hypothetical example, seven municipalities are part of a new regional entity. Using information from financial statements, we know that these seven municipalities spend about $33.8 million a year in public works programs. Under the new regionalization approach, these budgets (including employees) would be under the authority of the new entity. The new entity would then be responsible for operating garbage disposal services in all seven municipalities. We know that consolidations like this typically yield between 15%-20% savings in other states; thus, in this case, the regional entity would save almost $7 million. Those savings could be used to provide more services to the residents of those municipalities.

It’s difficult for mayors to accept that under this type of regional approach, they would lose direct control of a portion of their budgets. But there is really no point in creating regional entities if municipal operations, and hence costs, stay the same. Otherwise, it is another layer of inconsequential government.

Commonwealth Agency Savings

If the proposal transfers responsibility and budget authority of Agency programs to a new regional entity (i.e., ADFAN programs), Agency regional costs must be reduced. For example, if a regional entity is created with ten participating municipalities, and there is one ADFAN office in each municipality, regional offices would need to be reduced to achieve cost savings.

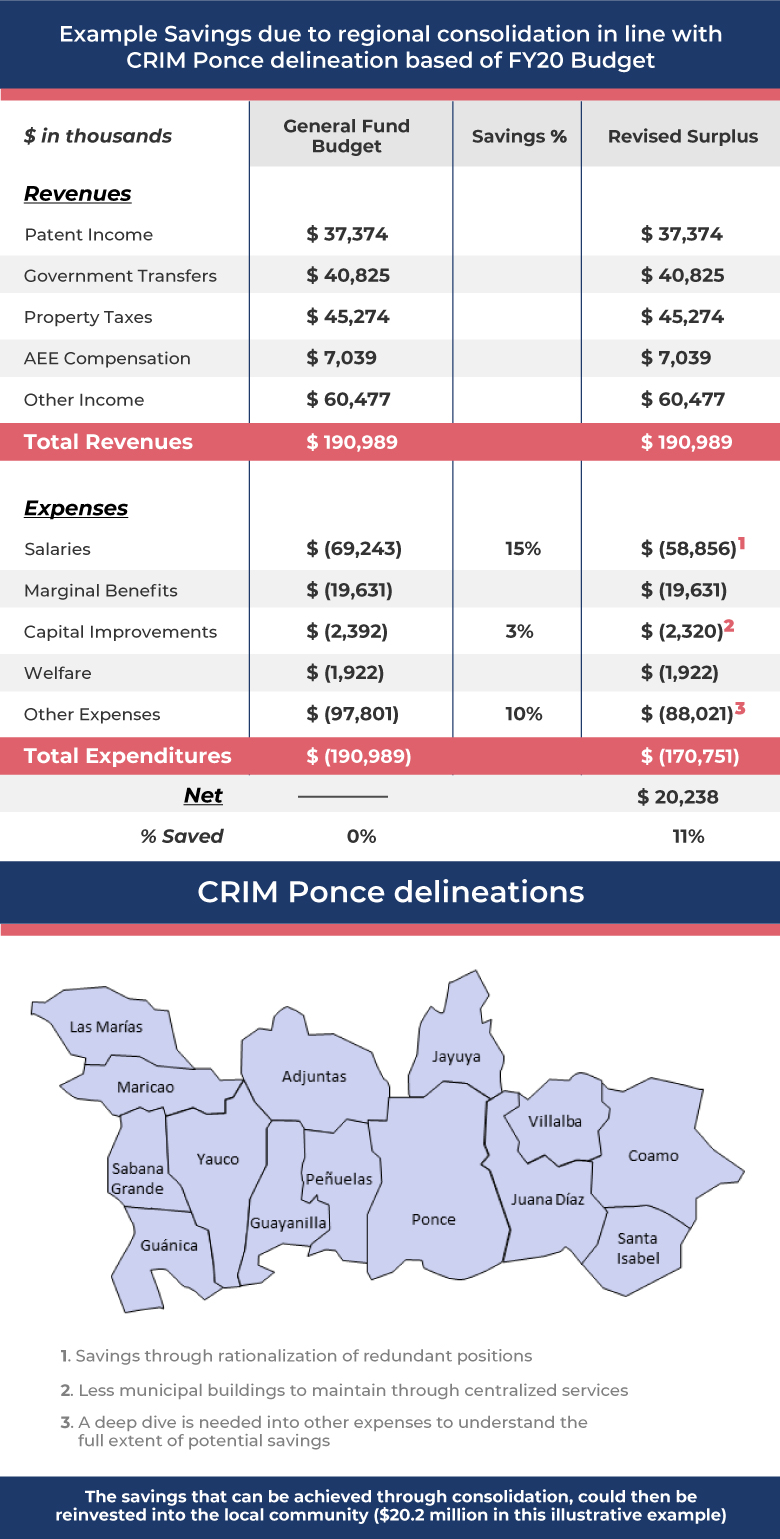

Exhibit E

Sample of Potential Service Consolidation: Regional Offices

In this case, we used the Ponce CRIM region only because we had more data at hand. By closing several CRIM offices in this region, the Commonwealth could save up to $20 million from the central government’s budget.

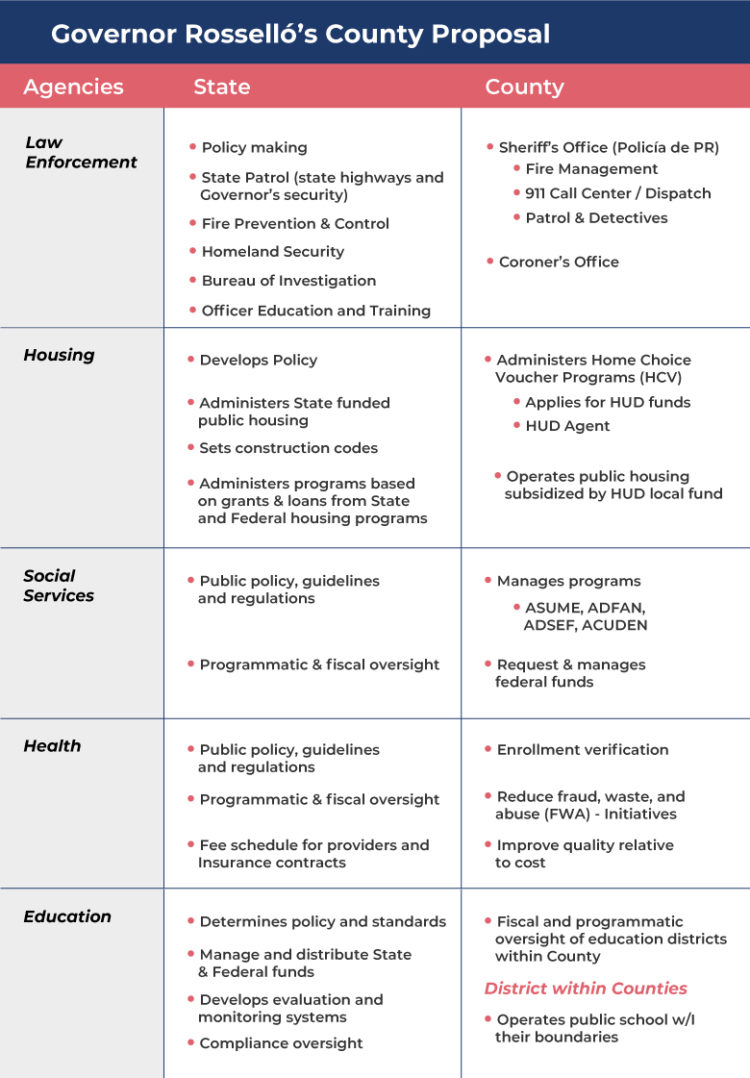

There are many questions around the types of Commonwealth programs that could be delegated to these new regional entities. Former Governor Rosselló sketched out an initial architecture (see Exhibit F). Some of these programs, like, state police, HUD funding, ASUME, ADFAN, and ADSEF, seem reasonable. But the development of any such proposal will require additional engineering, discussions with mayors, government officials, and other stakeholders. Some of the programs that involve federal funding would also require discussion with the government’s counterparts in the federal government.

Exhibit F

Governor Rosselló’s County Proposal

Funding of New Regional Entity

Costs associated with funding any new regional entities would need to come from municipalities’ budgets (cost savings) or any cost savings associated with Agency service restructuring. The two service consolidations discussed above would yield enough savings to fund the operations of the entity. As well, in order for such an entity to operate existing programs like public works for all municipalities in the region, it would require having the revenues that now go to municipal governments for such purposes.

- There are a lot of questions about the mechanics of funding: Whether municipalities transfer budgets to the new entity (very risky) or whether revenues from CRIM, SUT, and the Commonwealth go directly to the regional entities. This is something that must be modeled and discussed with mayors and other stakeholders. As well, there would be questions around the composition of these regions. The Commonwealth already has regional boundaries at many agencies, which could provide a good baseline. One recommendation is to allow flexibility in the process to ensure changes to the composition of a regional entity can be made without having to amend the statute in the future. An administrative process can be utilized instead. Having such flexibility will help accelerate a potential legislative process since legislators are not going to be stuck looking for the perfect regional composition.

The New Role of the Municipal Government

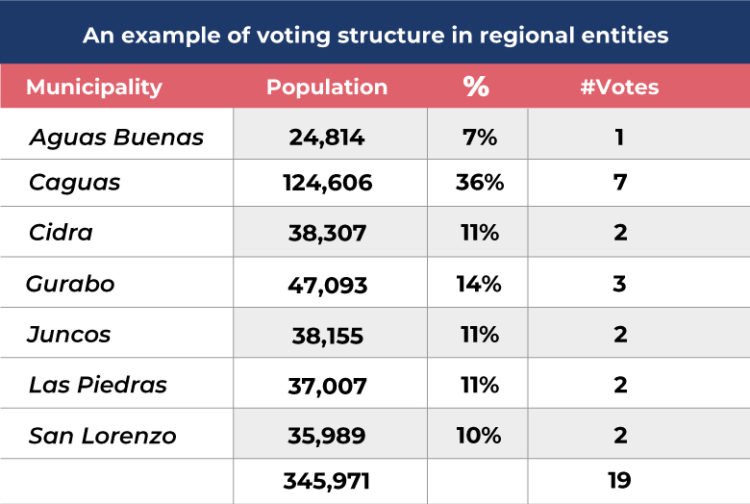

To be clear, the Oversight Board does not advocate for eliminating municipal governments. Mayors must play a key role in modernizing the Commonwealth’s outdated government structure. But their roles might have to change, focusing their energy and resources towards leadership, vision, advocacy, and oversight. For example, the mayors who comprise the discussed regional entity would have the responsibility of directing programs, with more focus on strategy. Should the regional entity pilot welfare to work programs, or open new charter schools? Should the region invest more on health prevention programs? Or start a new bus route between Arecibo- Aguadilla? In this example, the mayors would be in charge of establishing those priorities for the region. To enable such policy influence, the described regional entities could be governed by a board of directors, comprised of mayors of municipalities in those regions. Instead of one mayor-one vote, it might be more equitable to have the mayor’s vote be proportional to population or revenues. For example, using the same group of municipalities from Exhibit G, we can illustrate one example, although there are many more approaches. The important thing is that under this model, mayors would have more control over Commonwealth programs, which would lead to more benefits for their constituents.

Exhibit G

An example of a voting structure in regional entities

In this example, the board of this new entity (the mayors) would be in charge of selecting and supervising the executive officer or CEO. We believe the mayors will have a strong incentive to select a competent person since they will be competing for funding with other regional entities. Besides, with the decentralization of Commonwealth programs, one should expect more transparency and accountability, since it would be easier to track funding and services.

This model would have the scales to enable competition among regional entities around efficiencies and effectiveness of programs, which is hard to do now in the central government. The establishment of regional structures could also enable innovation and program experimentation in the government. You might see regions figuring out ways to improve DMV services or improving the health outcomes of residents through innovative public health programs. Other regions could learn and benefit from seeing the implementation of other approaches.

Where to start?

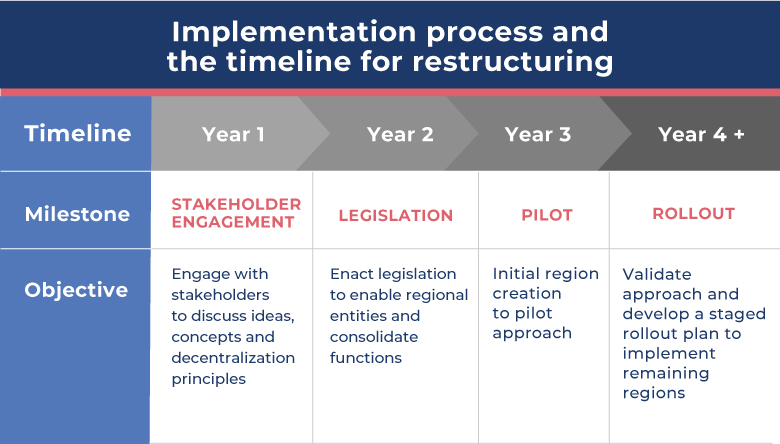

After stakeholder discussion and development of a proposal, the legislation would be required. While voluntary initiatives can facilitate some of these reforms, a comprehensive statutory overhaul must lay a solid foundation for sustainable progress. Any proposed legislation should include a pilot within one region of Puerto Rico to validate the approach and develop a staged rollout plan.

Below is a possible timeline.

Exhibit H

Implementation Process and the Timeline for Restructuring

Given the importance of this transformation, the Oversight Board is committed to helping the government and all the municipal governments throughout this process, with ideas, insight, and design support. This essay is just the beginning of a longer conversation. We welcome other ideas and look forward to the conversation.