While being major players of the economy, many small businesses are unable to weather a crisis like the one caused by COVID-19. Very small businesses, particularly those operating on small profit margins, are especially vulnerable, since they may not have the cash reserves and typically have fewer ways to access financing.

Authors: Olivier Perrinjaquet & Arnaldo Cruz, FOMB's Research and Policy Dept.

→ Although we recognize the CW’s strategic goals in the plan, careful design and implementation will determine the success of these programs. High-quality program design and implementation are critical to achieve intended outcomes. Implementation should also be periodically monitored as the programs are delivered to adjust their implementation as needed. There have been a lot of programs that have failed throughout history despite their good intentions due to inadequate, and ill-advised design and implementation. Moreover, these funds must be used strategically to maximize their positive effects on the preservation of businesses and jobs.

→ Finally, the Oversight Board encourages the involvement of seasoned NGOs and private financial institutions immersed in Puerto Rico’s business development and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Through a network of NGO organizations, the Commonwealth can spearhead a comprehensive intervention, with cash grants, technical advice, specialized consultancy, among other services to ensure the survival of many small businesses in Puerto Rico.

Acting quickly without a proper program design will limit the impact of these funds on the sector’s recovery.

To maximize the impact of these programs, whose funds need to be expended by the end of 2020, careful attention should be given to their design and implementation.

The Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB), fully cognizant of the unprecedented extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has threatened the health, safety, and livelihood of families and businesses across the island, has been actively looking for ways to support the government’s response efforts and mitigate the financial impact on residents and different types of business and commercial activities. It quickly approved $787 million in funding to support critical response efforts (Joint Resolution 23-2020), launched a website to provide a guide to the various federal and local resources available, and has consistently provided Puerto Rico’s policymakers with timely and targeted research and insight around various government programs to ensure a proper response and a swift recovery.

Given the importance of the micro, small, and medium-sized business (small business henceforth) sector in Puerto Rico’s recovery efforts and long-term economic development, this essay will expand on previous communications made by the FOMB on how to best help this critical sector during this challenging time. On April 24, 2020, the FOMB sent a letter to the Governor of Puerto Rico outlining some recommendations on how to best use the $2.2 billion the CW received on April 20, 2020 through the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund pursuant to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Two of the recommendations were related to economic development, the first one geared towards supporting the small business community, while the second one on how to reduce long-term unemployment.

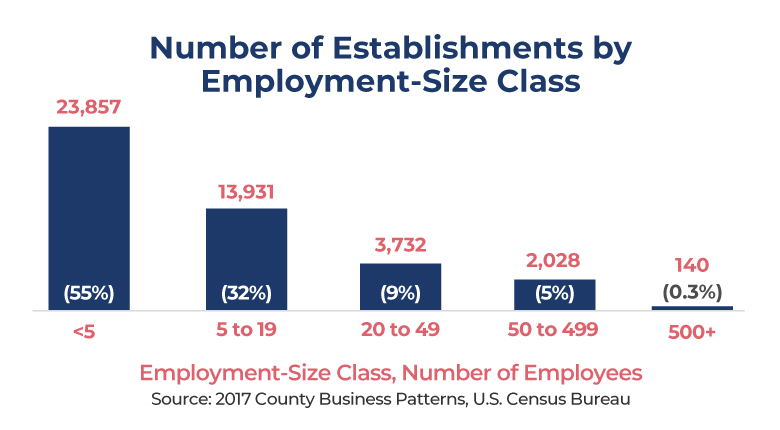

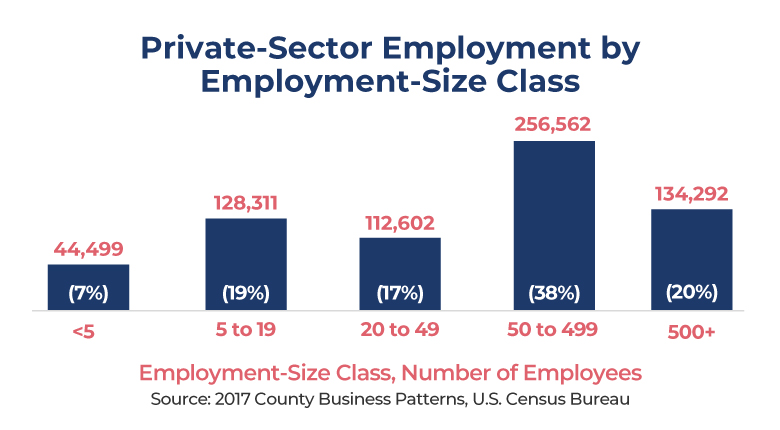

Small businesses, which have been among the most affected amid the pandemic-induced economic freeze, play a critical role in innovation, economic activity and growth, and job creation. They also increase the competitive structure of the economy’s different industries, creating a more dynamic business landscape and providing consumers with a wider array of goods and services. According to the 2017 County Business Patterns report published by the U.S. Census Bureau, micro-, small- and medium-sized businesses in Puerto Rico with less than 50 employees represent 95% of the total number of establishments, 42% of private sector employment, and 36% of total annual payroll (see graphs below).

Cash-strapped small businesses struggle to stay solvent amid the COVID-19 crisis and have an uncertain outlook.

While being major players of the economy, many small businesses are unable to weather a crisis like the one caused by COVID-19. Very small businesses, particularly those operating on small profit margins, are especially vulnerable, since they may not have the cash reserves and typically have fewer ways to access financing. According to a study of small businesses in the U.S. published in September 2019 using data from 2013 to 2017, 47% had two weeks or less of cash liquidity.

The strict lockdown measures established in Puerto Rico by executive order (Administrative Bulletin No. OE-2020-023) disproportionately affected small businesses since many large chains were able to maintain some level of business activity. In a survey of 719 small businesses in Puerto Rico published by Colmena66, 59% reported that they could remain open for less than a month with their available capital, while 31% could survive between one and three months.

COVID-19 has already taken a heavy toll on the small business community throughout the U.S. causing an avalanche of closures, albeit mostly temporary, and threatening many more. A U.S. Chamber of Commerce/ MetLife report, using data from a poll conducted between March 25-28, 2020, found that 54% of small businesses in the U.S. temporarily shut down due to the pandemic or would likely have to in the next couple of weeks. Furthermore, 43% do not think they can last six more months until they have no other choice but to shutdown permanently. Local surveys also point to widespread shutdowns. Colmena66’s survey found that in Puerto Rico 57% closed temporarily, 20% are partially operating, 10% are operating online, 5% are fully operational, 3% shutdown permanently, while 2% are on the brink of closure. According to the Puerto Rico Restaurant Association, there are approximately 4,000 restaurants in the island with annual sales of $1.97 billion, 50% of which are expected to permanently close due to the pandemic-induced economic crisis.

There is great uncertainty in the outlook for small businesses. According to a survey made by the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), which is the largest small business association in the country, most small business owners (63%) in the US, are not expecting the economy to fully rebound until sometime in 2021 or later. The MetLife/U.S. Chamber of Commerce survey found that 46% of small businesses believe that it will take between six months and one year for the U.S. economy to return to normal.

Policy and Government Response

The aforementioned reality being faced by the small business community highlights the urgent need of providing a lifeline to them. They need not only timely and effective grant and loan programs, but also technical assistance and capacity building to help them reinvent themselves given the radically changed business landscape caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Policymakers have been undoubtedly facing an unprecedented policy challenge. There is no playbook for them to follow on how to put the small business sector and other elements of the economy on life support for a prolonged period of time. Nevertheless, governments need to do everything they can to properly design and implement these small business programs which are critical for their continuity, job preservation, and economic stability.

The Federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) (Section 1102 of the CARES Act) is one of the main programs to support small businesses during the current economic turmoil triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak.

As part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Securities (CARES) Act enacted on March 27, 2020, $349 billion were allocated to fund a small business support program called the Paycheck Protection Program (Section 1102 of the CARES Act). The PPP is a fully guaranteed and potentially forgivable SBA loan program whose main policy is to help prevent mass layoffs and bankruptcies of eligible small businesses, self-employed individuals, sole proprietors, and non-profit organizations due to COVID-19. Since funds were exhausted in only a matter of two weeks given the high demand, Congress enacted the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, adding an additional $310 billion to the program, bringing the total to $659 billion.

The newly created PPP functions is in some ways similar to and in other ways different than other SBA programs. The PPP, like is the case for most of SBA’s loan programs (except disaster loans), is processed through SBA-approved commercial banks, credit unions, and specialized lenders. The SBA oversees the PPP, processing loan guarantees and forgiveness. On the other hand, SBA’s disaster loans, such as the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL), are processed through the SBA, meaning small businesses apply directly on the SBA’s website. Moreover, a key difference between PPP and other SBA loans is that the former is potentially entirely forgivable contingent upon how the money was spent. The loan under this program is forgiven if at least 75% of the loan is used to cover payroll and employee benefits costs, while the remaining 25% may be used for overhead costs including mortgage interest payments, rent, utilities, and other limited uses. Small businesses have eight weeks following the receipt of the loan to spend the funds. Congress is taking steps to make these requirements more flexible (H.R. 7010).

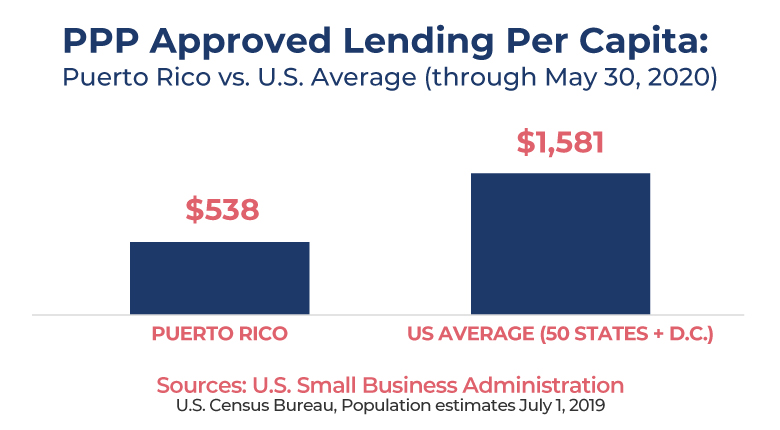

Puerto Rico has received, through May 30, 2020, $1.7 billion through the Paycheck Protection Program. This represents $538 dollars on a per capita basis, compared to an average of $1,581 in the 50 states and D.C.

While relatively few small businesses on the island applied to the PPP in the first round of funding, there was a significant uptick in the second round.

In the first round of the PPP (approved through April 16), approximately $659 million was loaned to 2,856 small businesses in Puerto Rico, for an average loan size of close to $230,000. In the second round an additional $1.06 billion was loaned to 28,563, for an average loan size of $37,100. This clearly shows that in the first round mostly bigger small businesses, which were better prepared and had the necessary documentation, applied to the loan program. In total (approved through May 30), $1.7 billion has been loaned to 31,419 small businesses in Puerto Rico for an average loan size of approximately $54,700.

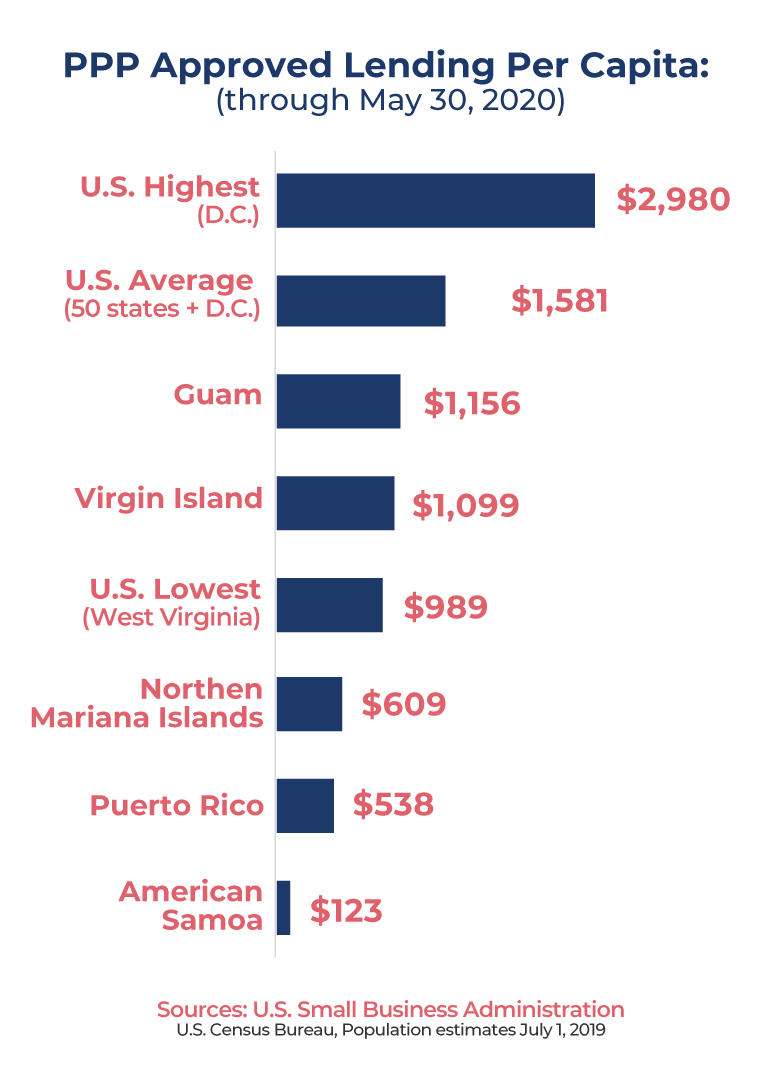

On a per capita basis, Puerto Rico received $538, which does not compare favorably to the 50 states and other US territories. (see graph below).

If Puerto Rico would have received the same amount of PPP dollars per capita as the U.S. average, it would have received close to $5.0 billion. Puerto Rico has historically lagged behind states in funds received through competitive federal programs. Following Hurricane Maria, the SBA reported that of 86,171 applications FEMA distributed to small businesses in Puerto Rico, 68,394 were never submitted. In the case of PPP, Puerto Rico might have received less funds per capita due to a number of reasons including (1) a lack of awareness or sophistication of potential applicants, and (2) only a very limited number of financial institutions (Banco Popular, FirstBank, and Oriental Bank) processed PPP loans in the first round since the SBA never sent the SBA-approved credit unions (i.e., cooperativas) the access code to be able to process loan applications.

Commonwealth’s Plan

The Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) (Section 5001 of the CARES Act), which provided $150 billion in direct assistance to governments in states, territories, and tribal areas, disbursed $2.2 billion to Puerto Rico.

The $2.2 trillion fiscal stimulus bill (CARES Act), the largest in US history, included assistance for state and local governments through the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund. Puerto Rico received $2.2 billion of the Coronavirus Relief Fund. On May 15, 2020 the CW announced how it will be using the funds, in accordance with the guidelines established by the U.S. Treasury. On May 25, 2020 the CW through AAFAF published the first weekly disbursement plan funding report.

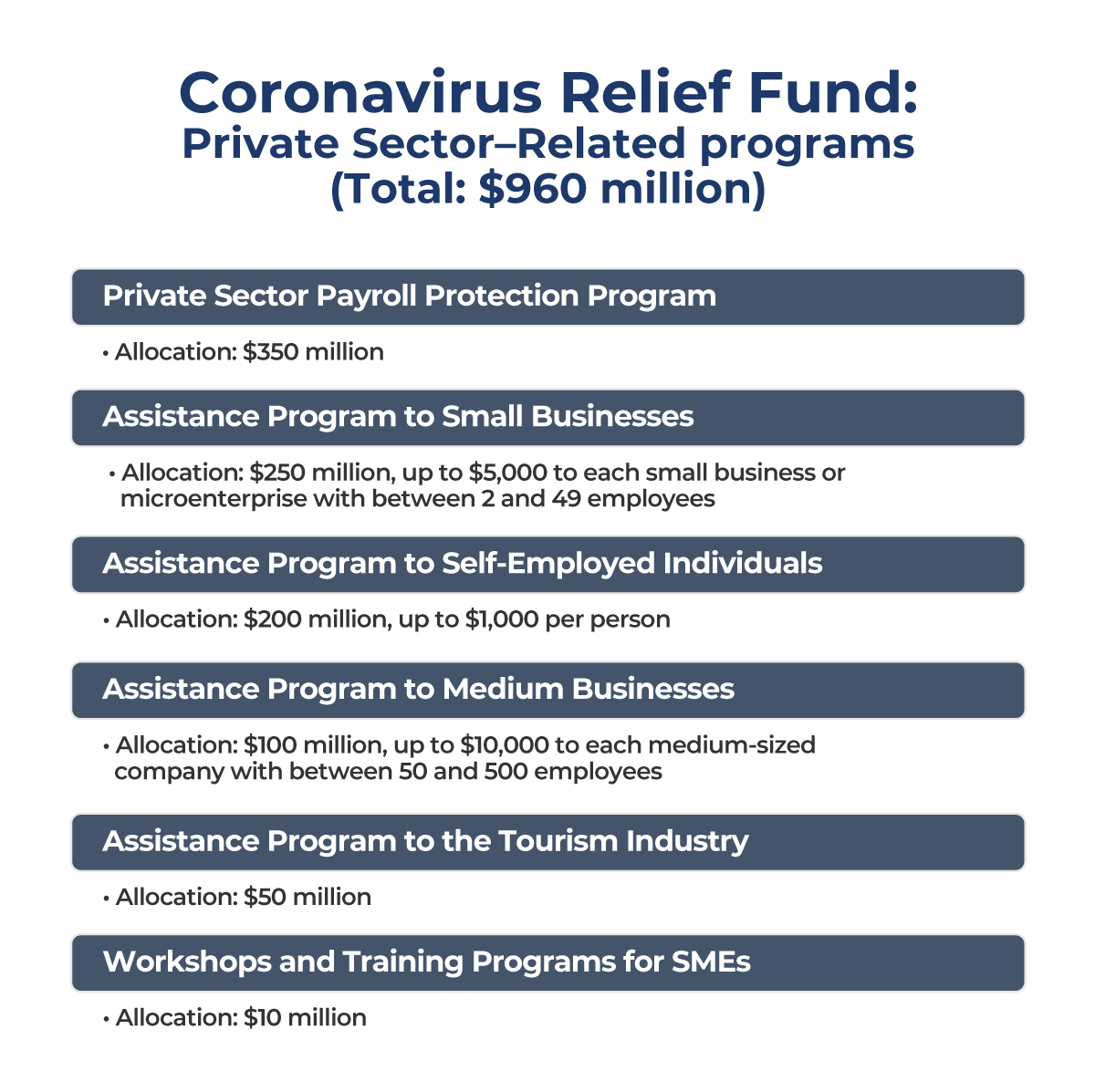

The CW announced it will direct the funds in three main areas: (1) strengthen capacity to address the COVID-19 pandemic (testing, contact tracing, isolation, and treatment), (2) ensure continuity of government services, and (3) reactivate economic activity and job protection. To stimulate the economy and protect jobs the CW will allocate CRF funds for private-sector related programs as follows.

Although we recognize the CW’s strategic goals in the plan, careful design and implementation will determine the success of these programs. High-quality program design and implementation are critical to achieve intended outcomes. Implementation should also be periodically monitored as the programs are delivered to adjust their implementation as needed.

There have been a lot of programs that have failed throughout history despite their good intentions due to inadequate, and ill-advised design and implementation. Moreover, these funds must be used strategically to maximize their positive effects on the preservation of businesses and jobs. Acting quickly without a proper program design will limit the impact of these funds on the sector’s recovery.

Given these concerns and risks, we provide specific recommendations on considerations when designing the private-sector related programs, starting with the local PPP program.

Lessons learned from the Initial Paycheck Protection Program (PPP): Adapting the local $350 million PPP to better meet the needs of small businesses on the island.

When designing the local $350 million PPP, the FOMB recommends the CW to incorporate the many lessons learned from the rollout of the initial PPP. Many of the imperfections of the original PPP are due to the fact that it was designed in a matter of weeks. Furthermore, the sheer volume of the loan program is extraordinary. To put it in perspective, in FY2019 the SBA total loan volume reached approximately $28 million, compared to PPP’s $659 billion. Now that policymakers have the experience of the initial roll-out and have received feedback and criticisms from small businesses, they can design it better to more effectively reach desired objectives.

- Shift in the program’s focus to the prevention of small business failure: The PPP program was originally designed when strict lockdown measures were in place which forced many businesses to close, triggering mass layoffs. This is why the initial focus of the program was to keep employees on payroll. Given changing needs and circumstances, the focus of the program should shift to helping small businesses prevent failure. Small businesses that rely on foot traffic during the workday, like restaurants for example, will see demand dry up as bigger corporations tell their workers to stay home. Additionally, high levels of unemployment are expected to persist even as the economy reopens, which will crimp consumer spending that small businesses rely on. As a result, when businesses begin to open, they will have significantly less customers and hence, will need fewer people to operate. With this in mind, bringing back all pre-lockdown employees should not be the goal of a PPP program, as small business owners should be allowed to stay as flexible as possible going forward into this “new normal.” Unneeded employees who desperately need cash assistance should instead receive unemployment insurance. Employees who were laid off due to COVID-19 are eligible to receive enhanced unemployment benefits (Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation providing $600 benefit in addition to regular benefits). Thus, limited, and finite CARES funds should not go to pay salaries of unneeded workers.

On the issue of unemployment benefits, there has been plenty of speculation about weekly federal payouts creating disincentives to work, which would complicate reopening businesses. For some employees, particularly in Puerto Rico, enhanced unemployment benefits are now larger than their wages. In the latest executive order, the governor indicated that employees that refuse to go back to work will be ineligible for unemployment insurance. While we recognize this measure as appropriate, looking forward, potential alternatives should be considered to allow flexibility to both employees and business owners. An innovative program known as “work-sharing”, also known as short-time compensation (STC) or shared-work program, currently available in 26 states covering roughly 70% of the U.S. workforce to prevent layoffs, assist employers during a downturn, and help them avoid search, hiring, and training costs once business picks up. Under this program, businesses reduce working hours of employees in a downturn rather than lay them off, and the workers receive pro-rated unemployment benefits. This program is intended for workforce reductions that are expected to be temporary. The CARES Act provided Puerto Rico with $439,000 for state administration and promotion of the STC program.

- Providing greater flexibility in the use of funds: For the PPP loan to be forgiven at least 75% of the funds need to be used for payroll, while the remaining 25% may be used for non-payroll expenses. An amount higher than 25% should be authorized to pay rent, utilities, inventory, and other non-payroll expenses. The U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed H.R. 7010 (417-1 vote) on May 28, 2020, the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act of 2020, reducing the 75% payroll requirement to 60% (non-payroll to 40%). The U.S. Senate quickly followed suit, giving unanimous consent on June 3, 2020. The bill was signed into law by the President in May 5. Many businesses also complained that they couldn’t rehire employees while closed but still had the burden of fixed overhead costs. These requirements for loan forgiveness are especially bad for small businesses with small payroll and large rent and utility obligations or for those who laid off workers prior to taking out the PPP loan. PPP loans should also be forgiven when used for investments in retrofitting to comply with COVID-19 related health and safety regulations.

- Extending the time to spend the loan money: The PPP required small businesses to spend the loan money in 8 weeks. When Congress designed the program, they were expecting the business landscape to go back to normal after eight weeks, but clearly this will not be the case. The time borrowers are allowed to spend the loans should be extended beyond 2 months, possibly until the end of the year. H.R. 7010 intends to extend the expense forgiveness period from 8 weeks to 24 weeks, or until the end of the year, whichever comes first. The bill also extends from two years to five years the time businesses have to repay the loan in case it was not forgiven.

- Ensuring a smooth and highly effective rollout of the program: The initial rollout of the PPP was plagued with technical delays and glitches, creating widespread confusion. The problems with SBA’s application processing site, E-Tran, frustrated lenders and borrowers alike, creating great uncertainty. To be fair, it should be noted that SBA launched the unprecedented program on April 3, 2020, just one week after the enactment of the CARES Act. Banks were overwhelmed by the number of applications and their systems could not withstand the demand. Nevertheless, small businesses, particularly given this time of great need and hurt, should have an unencumbered experience when accessing critical loan programs.

- Ensuring loans go to small businesses and not large firms: Large publicly traded companies and restaurant chains like Ruth’s Chris Steak House and Shake Shack were able to participate in the PPP. Some larger chains exploited a loophole in the law to participate as a small business. While SBA’s business loan program “affiliation rules” generally apply to PPP, the CARES Act waived the rules in some limited cases which ultimately allowed larger businesses to qualify to the program. The loan program should be directed to those small businesses who need it the most.

- Prioritizing Underserved and Rural Markets: SBA’s Inspector General reviewed the implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program and found that the SBA did not issue guidance to lenders to prioritize the markets indicated by Section 1102 of the CARES Act, suggesting that the SBA should “issue guidance to lenders requiring lenders to prioritize borrowers in underserved markets.”

- Tighter parameters prioritizing most vulnerable businesses with the least liquidity: While the program can be open to all small businesses, those with severe liquidity issues can be given higher priority.

- Ensuring good communication between the SBA, lenders, and borrowers: Many businesses that applied to the program through a commercial bank or credit union complained that it took too long for them to know if they were going to be able to participate in the program.

- Greater oversight and transparency of loan recipients: To promote accountability and stakeholder trust in the process, appropriate oversight mechanisms and greater transparency of loan recipients should be established. This will help identify any companies that improperly received funds. To prevent and minimize waste, fraud, and abuse, there should be clarity in how audits will be conducted, what standards apply, and what are the consequences of noncompliance.

- Minimize ambiguities in the program guidelines/ legislative text: Ambiguities in the legislative text of the CARES Act led to problems in computing the maximum loan proceeds and borrower’s debt forgiveness. Many applicants complained that payroll costs were poorly defined. Great clarity should be provided in program guidelines to prevent confusion and uncertainty.

- Adopting outcome-based program performance measures: To better determine the impact of small business programs like the PPP, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) recommended the SBA to use outcome-based program performance measures (how do the small businesses perform following SBA assistance) rather than output-based program performance measures (e.g., number of loans approved and funded). The performance of small businesses participating in the local PPP should be monitored to determine the effectiveness of the program and to better design future small business assistance programs.

Cash Grant Programs

Proper Design and Implementation of Small and Medium Sized Business Grant Programs is critical to maximize desired program objectives.

In times of economic distress like the one being experienced in Puerto Rico due to the COVID-19 outbreak, direct cash grant programs are a natural go-to solution to help small businesses avoid being shuttered, retain employees, rebuild, and recover. Understandably, there is great demand for these programs among the small business community following disasters.

Part of the $2.2 billion in federal funds the CW received through the Coronavirus Relief Find pursuant to the CARES Act will be allocated for cash grant programs for small and medium sized businesses: $250 million is allocated for micro and small businesses with between 2 and 49 employees, while $100 million will be disbursed to medium-sized business with between 50 and 500 employees. Micro-, and small-business may receive up to $5,000 while medium-sized businesses may receive up to $10,000 per business.

To maximize the impact of these programs, whose funds need to be expended by the end of 2020, careful attention should be given to their design and implementation. In this section we provide some guidance and recommendations on how these programs may be best designed and implemented by looking at best practices and success stories locally and in the states.

Several local NGO’s have implemented cash grants programs for small businesses in Puerto Rico. Most have partnered with other organizations to enhance capacity and combined the cash with technical assistance. Most of those programs also required a needs assessment prior to distributing cash to businesses. A number of states and local governments have enacted legislation creating small business cash grant programs to assist businesses in the COVID-19 context. Below are specific recommendations on how to design and implement the cash grant programs for small and medium-sized businesses, based on the experience in other states and FPR’s Small Business Cash Grant Program.

- Grants should be disbursed in phases rather than in a one-time lump sum: There is great uncertainty of where the economy will be in the short- and medium-term. To maximize the effectiveness of the program, especially given the large amount of funds that will be mobilized, it would be prudent to disburse the funds in stages to see how the economy performs and what are the needs of the small businesses. New Jersey, through its New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA), initially launched a $5 million Small Business Emergency Assistance Grant Program on April 3, 2020. The program was oversubscribed within an hour. Given the large demand, a Phase 2 of the program was launched.

- Strategically selecting participants: Should grant applications be processed on a first-come, first-serve basis or should we have a discriminatory policy with fund disbursements? If the first come-first serve route is followed, funds could be misallocated since they might not go to businesses that needed it the most or to those who are most likely to survive. In Michigan’s Small Business Relief Program, local and nonprofit economic development organizations (EDOs) around the state administered the program, reviewing applications and conducting a needs assessment to every applicant. After reviewing applications, each EDO provides a list of grant winners to the Michigan Development Corporation, the state’s economic development entity. In the Michigan program, the EDO’s are also responsible for disbursing funds to grantees as well. In New Jersey, the state’s Economic Development Authority set aside $15 million for businesses in Opportunity Zone-eligible census tracts. The Denver Economic Development and Opportunity (DEDO) gave priority in the cash grant program to industries most affected by the pandemic (e.g., the food and restaurant industry).

- Partnering with NGO’s and CDFI’s: The lead agencies for this program are the Department of Treasury, Department of Labor and the DDEC. However, the Oversight Board encourages the involvement of seasoned NGOs and private financial institutions immersed in Puerto Rico’s business development and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Accessing and servicing businesses that are most affected by the pandemic could be best achieved by sharing the outreach and execution of this program with the NGO community in Puerto Rico. Engaging with an established group of NGO’s with existing business network and infrastructure, then further overlaying a transparent framework grounded in partnership, regular reporting, and accountability will best serve the Government and the people of Puerto Rico. In addition, a locally based response has proven to be more effective at providing the necessary support and assistance in our communities. In Wisconsin, the Economic Development Corporation partnered with the state’s 23 community development financial institutions (CDFIs). Given the strong relationships CFDIs have with their clients, the funds have been deployed rather quickly. As in the Michigan program, funding decisions and actual technical assistance services should involve local Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI’s) and NGO’s, rather than solely relaying on government agencies to implement the program. This will also ensure rapid deployment of the program. As way of example, the small business programs under Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program (CDBG-DR) have taken too long to launch. In March 2020, almost three years after Hurricane Maria, the Department of Housing finally announced the launch of several small business programs in partnership with DDEC and Economic Development Bank (EDB).

- Transparency in grant recipients: For the sake of accountability, transparency and public trust, a list of grant recipients should be made publicly available as has been done in New Jersey’s Small Business Emergency Assistance Grant Program and Michigan’s Small Business Relief Program.

Capacity Training to SME’s

The CW has also allocated $10 million from the Coronavirus Relief Fund for training programs and workshops for SMEs, self-employed and entrepreneurs on doing business during COVID-19 in compliance with public health requirements and orders.

For many small business owners, devising a new path forward in this challenging context is a daunting task and they can benefit greatly from the training and coaching from seasoned local nongovernmental organizations. FOMB welcomes the $10 million allocated for training and workshops for small and medium sized enterprises (PYMES) to ensure that they conduct their business in accordance with the new public health rules and requirements. However, small businesses will also need technical assistance to help them devise a new way forward in this new COVID-19 reality. They need assistance in strategic planning, building capabilities in digital marketing and sales, managing supply chain risk and disruption, optimizing staff management, among other business domains. Depending on the type of business and location, the strategy for reopening post-coronavirus may look very different for small businesses across the Island, even within the same neighborhood. Companies will need to adapt their business models both out of necessity and opportunity. For example, retail stores, which have seen their offline stores close around the world, have moved to target potential customers with online activities to increase sales. Restaurants, which are and will be unable to operate as they were before the crisis, will need expand their delivery options to reach more customers. Some restaurants might have to expand their business to include more prepackaged items and family meal options. Gyms might have to go from teaching Zumba at their locations to having multiple Zoom workouts a week.

Undoubtedly, Covid-19 has highlighted the importance of e-commerce and the need for businesses to improve their online presence for customers. As consumer habits change, small businesses will have to continue to improve their e-commerce platforms and find efficient ways to distribute their products to consumers. But that means that business owners will need to devote more attention to understanding their customers through advanced sales and web analytics. Thus, liquidity and lack of capital will not be the only challenges hindering small businesses under this new economic reality. The biggest challenge will be the failure to look forward. This is why part of the support package should include hands-on and customized guidance to small business owners on business planning, finance, loan preparation and more. As well, as the coronavirus crisis has accelerated the uptake of digital solutions, tools, and services, the lack of tech or e-commerce savviness will hurt small businesses the most during the new reality. Training programs on social media and integrating and managing e-commerce will be necessary. It is still possible to allocate incremental funds or include in the announced spending allocations this type of partnership with NGOs to provide assistance.

Through a network of NGO organizations, the Commonwealth can spearhead a comprehensive intervention, with cash grants, technical advice, specialized consultancy, among other services to ensure the survival of many small businesses in Puerto Rico.